15 tech luminaries we lost in 2024

The computing industry was founded with mainframes intended for the few. Bringing computers to the masses was the work of generations, such as the trailblazers we honor in this story. Whether they shrank transistors, crafted new programming languages, or connected people online and off, these software developers, hardware designers, and business executives took expensive, inscrutable technologies and made them accessible to all.

As Computerworld looks back at 2024, we celebrate the lives and accomplishments of these fifteen remarkable IT pioneers who passed away this year — but not before leaving their mark.

Niklaus Wirth: Pascal pioneer

February 15, 1934 – January 1, 2024

Niklaus Wirth

Tyomitch

After earning a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, followed by master’s and Ph.D. degrees, Niklaus Wirth began his career in teaching — first at Stanford University, then at his undergraduate alma mater, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), where he remained from 1968 until his retirement in 1999.

When tasked with starting the school’s computer science department, Wirth found the programming languages available at the time too complex — so he created his own. He released Pascal and its source code to the community in 1970 and introduced it to the classroom in 1971.

The result was a success, recalled Wirth: “It allowed the teacher to concentrate more heavily on structures and concepts than features and peculiarities — that is, on principles rather than techniques.” Pascal became an introduction to programming for generations of students — though it was not merely an academic exercise.

“I do not believe in using tools and formalisms in teaching that are inadequate for any practical task,” said Wirth. “[Pascal] represented a sensible compromise between what was desirable and what was effective.”

During his time at ETH, Wirth took two sabbaticals to work at Xerox PARC. There, he encountered the Alto computer, his first time using a personal computer that he didn’t need to timeshare with others. The experience inspired him to return to Switzerland and build his own personal computers and their accompanying software. Languages he developed for these computers included Modula-2 (1979) and Oberon (1988). Ultimately, Wirth was his own best student: “One learns best when inventing,” he said.

Wirth was honored in 1984 with ACM’s Turing Award and in 2004 as a Computer History Museum Fellow. He died at 89.

John Walker: Design revolutionary

May 16, 1949 – February 2, 2024

John Walker

Shaan Hurley

John Walker didn’t find his success overnight: the son of a doctor and a nurse, he studied astronomy before switching to electrical engineering; founded the hardware company Marinchip Systems in 1976; and then co-founded Autodesk in 1982. The company’s first product was an eponymous office automation program.

It was AutoCAD that finally gave Autodesk and Walker their fame. Walker didn’t invent computer-assisted design — the term “CAD” was coined in 1959 — but previous CAD software had largely been limited to more powerful mainframe computers; AutoCAD was one of the first implementations to be available to the masses.

Originally developed as Interact CAD, AutoCAD was demoed for CP/M computers at the 1982 Comdex industry trade show, where it was met with wild acclaim. It ushered in a design revolution in architecture, engineering, interior design, manufacturing, and more. AutoCAD is still used and supported today, with the latest version having been released for Windows and macOS in May 2024.

Walker himself was a talented software developer and author who enjoyed writing more than he did managing: shortly after Autodesk went public in 1985, he stepped down as CEO. He moved to Switzerland in 1991 and retired in 1994 at the age of 45.

In retirement, Walker wrote many books, including The Hacker’s Diet: How to Lose Weight and Hair Through Stress and Poor Nutrition (which, “notwithstanding its silly subtitle, is a serious book about how to lose weight,” wrote Walker); and The Autodesk File: Bits of History, Words of Experience, an 889-page PDF that saw its fifth and final revision in 2017.

Walker was 74 when he died from head injuries sustained from a fall at home.

Herbert Kroemer: Taking big steps

August 25, 1928 – March 8, 2024

Herbert Kroemer

Javier Chagoya

Some inventors have ideas ahead of their time; it takes decades for technology and society to catch up. That’s why it wasn’t until 2000 that Herbert Kroemer received the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in heterostructures dating back to the 1960s.

Kroemer earned his Ph.D. at the age of 23 before joining a semiconductor research group in the German postal service in 1952. Charged with improving the rate and reliability of transistors (still fairly new at the time, having been invented in 1947), Kroemer proposed improvements that required technology that did not yet exist. Kroemer’s proposals were eventually implemented in what became known as heterostructure transistors.

In 1963, while working at one of Silicon Valley’s first high-tech companies, Varian Associates, Kroemer recommended using heterostructures for lasers as well, enabling them to operate continuously at room temperature. He received the patent for his idea in 1967, which led to the creation of laser diodes — a technology with applications both small (disc players, barcode scanners) and large (satellite communications, fiber optics).

In 1976, after eight years on the faculty at the University of Colorado, Kroemer moved to University of California, Santa Barbara, where he remained until his retirement in 2012.

Kroemer once said, “Small steps didn’t really interest me. I was interested in big steps.” Those big steps earned him not only the 2000 Nobel Prize, but also the 2001 Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany and the 2002 IEEE Medal of Honor. He was 95 when he passed.

Daniel C. Lynch: Making connections

August 16, 1941 – March 30, 2024

Daniel C. Lynch

Informa Tech

Bringing people and ideas together and assuring they work well is what good leaders do. And that’s what Daniel Lynch did throughout his career.

After earning a master’s degree in mathematics, Lynch worked in the United States Air Force, where he learned to program. That skill set led him to positions at Lockheed Martin and then Stanford Research Institute, where he encountered the ARPANET. The precursor to the internet inspired his passion for computer networking, and he helped replace the ARPANET’s NCP protocol with TCP/IP, offering broader compatibility and networking.

Nonetheless, early internet developers proliferated a variety of incompatible applications and protocols. To get them all talking to each other, Lynch founded Interop, an annual conference that launched in 1986 with internet pioneer Vint Cerf as the keynote speaker. The show was an instant success, providing a much-needed space for direct communication among industry peers.

One of the early draws of Interop was the InteropNet, a local-area network (LAN) consisting of 120 miles of wires connecting 7,000 machines. With each of the show’s vendors being part of the InteropNet, it was an opportunity to test how hardware and software from different manufacturers would or could talk to each other. Interop also published 117 issues of a monthly technical journal, ConneXions (1987–1996).

Interop was sold to Ziff-Davis in 1991 and merged with their Networld event in 1994; the conference became known as Networld+Interop until 2005, when it again adopted the name Interop. The show hit its peak in 2001 with 61,000 attendees.

In 1994 — one year before he left Interop, and four years before PayPal was founded — Lynch co-founded CyberCash, an online payment service. CyberCash filed for bankruptcy in 2001 and was acquired by VeriSign — then, in 2005, by PayPal.

Lynch was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame in 2019. He died at 82 from kidney failure.

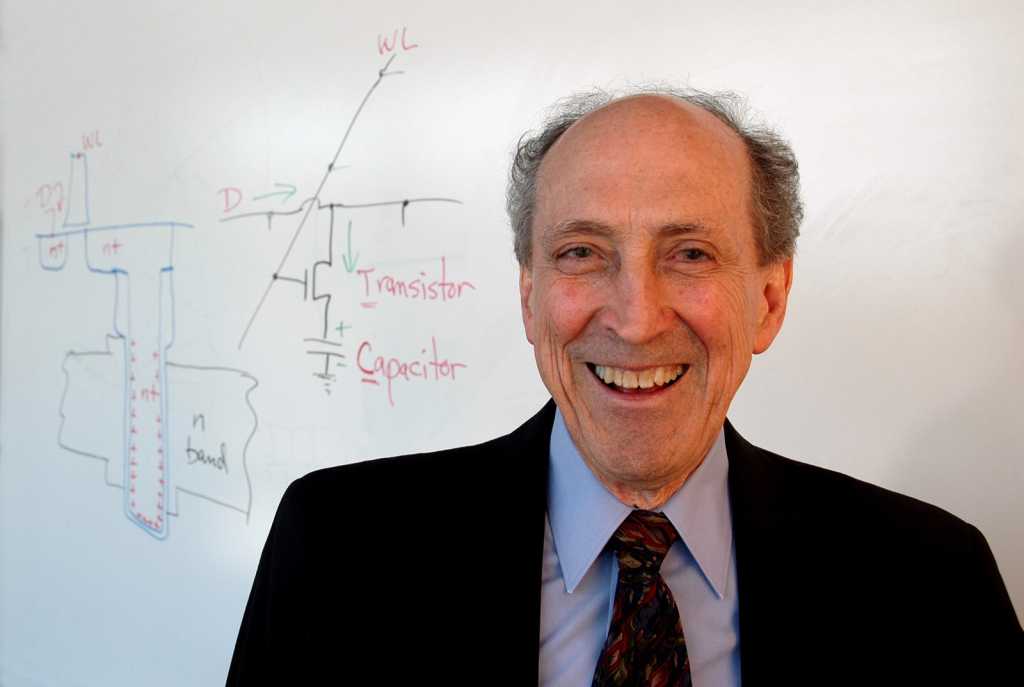

Robert Dennard: Memory man

September 5, 1932 – April 23, 2024

Robert Dennard

Fred Holland

Entering college on a French horn music scholarship, Robert Dennard earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering. He then joined IBM as a researcher in 1954.

At that time, storing a single bit of information in memory required six transistors — a relatively expensive and limiting technique. In 1966, Dennard delivered dramatic improvements in speed and capacity when he invented the one-transistor memory cell. This design became the basis for dynamic RAM, or DRAM, which is used in practically all computing devices to this day.

Dennard also worked on metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs). In a 1974 paper he co-authored, Dennard described how transistors could become smaller (in accordance with Moore’s Law) while retaining the same energy consumption — a principle that became known as Dennard scaling.

Dennard’s innovations earned him the United States’ National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 1988 and the Kyoto Prize in Advanced Technology in 2013. Yet Dennard remained humble, saying, “I’m a very ordinary person, with a very ordinary background and upbringing… It’s not enough to just think creatively. Once you’ve posed the question, you’ve got to answer the question.”

Dennard stayed at IBM until his retirement in 2014. He died at 91 from a bacterial infection.

C. Gordon Bell: VAX visionary

August 19, 1934 – May 17, 2024

C. Gordon Bell

Queensland University of Technology

In 1958, after returning to the USA from a Fulbright scholarship teaching computer design in Australia, Chester Gordon Bell enrolled in a Ph.D. program at his undergraduate alma mater, MIT. But Bell was lured by Digital Equipment Corporation to drop out of school in 1960 and become DEC’s second-ever engineer. There, he contributed to the architecture of the PDP-1, PDP-5, and PDP-11 minicomputers and was the principal architect of the PDP-4 and PDP-6. The PDP-1 was DEC’s first computer, and although only about fifty were manufactured, it paved the way for the commercial success of later models.

After a six-year hiatus to teach at Carnegie Mellon University, Bell returned to DEC in 1972 as vice president of engineering. During this stint, Bell co-architected and oversaw the development of the VAX series of “superminicomputers,” as DEC referred to them. Along with the PDP line, the VAX computers were so successful, they led DEC to become the industry’s second biggest computer manufacturer.

In 1983, Bell had a heart attack, which he blamed on the stress of working for DEC’s often overbearing co-founder, Ken Olsen. Bell retired from DEC — but his career stretched on for decades more. He went on to be an assistant director at the National Science Foundation; vice president of research and development at Ardent Computer; and principal researcher at Microsoft, where he championed lifelogging — recording and storing every aspect of one’s life digitally.

Bell also co-founded what is now the Computer History Museum of Mountain View, California; established the ACM Gordon Bell Prize to honor innovations in high-performance computing; and was granted the National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 1991. He died at 89 from pneumonia.

Lynn Conway: Breaking down barriers

January 2, 1938 – June 9, 2024

Lynn Conway

Charles Rogers

While working at IBM on the Advanced Computing Systems project in the 1960s, Lynn Conway developed dynamic instruction scheduling (DIS), a computing architecture technique that enabled computers to perform multiple operations simultaneously, paving the way for the first superscalar computer.

Conway’s reward: she was fired from IBM and all record of her work expunged — all because she’d come out to her employer as being transgender. With her career erased, Conway underwent gender-affirming surgery and began a new career under a new name.

Despite the professional setback, Conway continued building a legacy of profound innovations. In 1973, while working at Xerox PARC with Carver Mead and Bert Sutherland, she co-developed very large-scale integration (VLSI), enabling microchips to hold millions of circuits — kicking off a revolution in computer architecture and design. She returned to MIT, a school she’d previously dropped out of in the 1950s after a physician threatened her with institutionalization, to teach the university’s first VLSI design course.

Related reading: Unsung innovators: Lynn Conway and Carver Mead

Conway then worked at DARPA before joining the faculty of the University of Michigan, where she remained for 13 years until her retirement in 1998. She did not come out about her work at IBM until 2000, after which she became an outspoken advocate for transgender rights. Conway was heartened by the changing landscape compared to when she grew up, saying: “Parents who have transgender children are discovering that if they… let that person blossom into who they need to be, they often see just remarkable flourishing of a life force.”

In 2020, fifty-two years after Conway was fired, IBM issued a formal apology.

She passed away at the age of 86 from a heart condition.

Trygve Reenskaug: A model for success

June 21, 1930 – June 14, 2024

Trygve Reenskaug

Trygve Reenskaug

When Xerox PARC developed the Alto computer in 1973, it debuted a new paradigm: the graphical user interface (GUI), an abstraction between the user and the computer’s underlying data. To develop GUI programs, developers also needed a new model to work with.

University of Oslo computer science professor Trygve Reenskaug was visiting PARC in 1979 when he came up with the solution: the model-view-controller (MVC) pattern. Originally designed in Smalltalk, an object-oriented language that was developed at PARC from 1972 to 1980, MVC eventually became popular for developing web applications, including in Ruby on Rails.

MVC wasn’t Reenskaug’s only innovation: in 1963, he developed an early CAD program, Autokon, which was widely used in maritime and offshore industries. And in 1986, he founded software company Taskon, where he developed the software package OOram (Object-Oriented role analysis and modeling). OOram later evolved into data, content, and interaction (DCI), a software development model that continues to be used to this day, such as in Tinder’s mobile app.

Reenskaug remained humble about his contributions, writing, “I have sometimes been given more credit than is my due.” He cited teammates Alan Kay, Jim Althoff, Per Wold, and Odd Arild Lehne, among others, who carried the baton before and after him.

Reenskaug was 93 when he died.

Bruce Bastian: Perfecting the word

March 23, 1948 – June 16, 2024

Bruce Bastian

B W Bastian Foundation

In 1979, while earning his master’s degree in computer science at Brigham Young University, Bruce Bastian partnered with his professor, Alan Ashton, to co-found Satellite Software International. Their flagship product was word processing software that they had co-developed for the city of Orem, Utah. That program later became the new name of their company: WordPerfect Corporation.

The WordPerfect software debuted several innovations, including function-key shortcuts, numbering of lines in legal documents, and a scripting capability. It went toe-to-toe with Microsoft Word, trouncing it in the MS-DOS era but proving slow to catch up in Windows, where Microsoft bundled Word in its Office suite. But over the years, versions of WordPerfect also proliferated for Atari, Amiga, Unix, Linux, Macintosh, and iOS devices.

WordPerfect was acquired by Novell in 1994 and by Corel, now Alludo, in 1996. Only the Windows version is still supported, having been most recently updated in 2021; it remains popular, especially among lawyers.

Bastian left the Mormon church in the 1980s when he came out as gay. He became a staunch advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights, sitting on the board of the nonprofit Human Rights Campaign and donating $1 million to defeat California’s Proposition 8 to outlaw same-sex marriage in 2008. His own nonprofit, the B.W. Bastian Foundation, continues to support organizations that further human rights and the LGBTQIA+ community.

“I’m doing this for the kid in Idaho, growing up on a farm. I don’t want him to go through the s— I went through,” Bastian told the Salt Lake Tribune.

Bastian died at 76 from complications associated with pulmonary fibrosis.

Lubomyr Romankiw: Magnetic personality

April 17, 1931 – June 27, 2024

Lubomyr Romankiw

Qhuang75

Born in Zhovkva, Ukraine (then part of Poland), Romankiw emigrated to Canada, where he attained citizenship and earned his bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering. After earning a master’s and Ph.D. in metallurgy and materials in 1962 from MIT, he joined IBM.

At that time, IBM’s mainframes relied on drum storage for memory, which was slow, heavy, expensive, and limited to a few hundred kilobytes. In the 1970s, Romankiw partnered with co-worker David Thompson to invent magnetic thin film storage heads. The innovation spanned almost a dozen patents that reduced the size and increased the density of data storage devices. Any modern device that uses magnetic-head hard drives (as opposed to solid-state drives) still employs Romankiw’s innovations. His work earned him a place in the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2012.

Romankiw spent his entire career at IBM, earning the rank of IBM Fellow in 1986. He also became a Fellow of the Electrochemical Society in 1990. Among Romankiw’s other developments and 65 patents were inductive power converters and inductors for high-efficiency solar cells.

He was 93 when he passed.

Susan Wojcicki: Channeling innovation

July 5, 1968 – August 9, 2024

Susan Wojcicki

TechCrunch

When Larry Page and Sergey Brin founded Google in 1998, they needed office space. Management consultant Susan Wojcicki provided her garage — and, over the years, so much more.

Hired as Google employee #16, Wojcicki went on to play several defining roles in the company: she was Google’s first marketing manager in 1999; she product-managed the launch of Google Image Search in 2001; she was AdSense’s first product manager in 2003; and, while heading the nascent Google Video division, she initiated and managed Google’s acquisition of competitor YouTube in 2006.

In 2014, Wojcicki was appointed CEO of YouTube. Over the next nine years, she oversaw the service’s expansion into multiple countries, languages, and brands, including YouTube Premium, TV, Shorts, Music, and Gaming. The platform’s annual advertising revenue now exceeds $50 billion.

Throughout her career, Wojcicki’s work embodied the early days of Google, which she defined as “incredible product and technology innovation, huge opportunities, and a healthy disregard for the impossible.” She stepped down as YouTube CEO in February 2023, remaining in an advisory role at parent company Alphabet. She passed away 18 months later at age 56 from lung cancer.

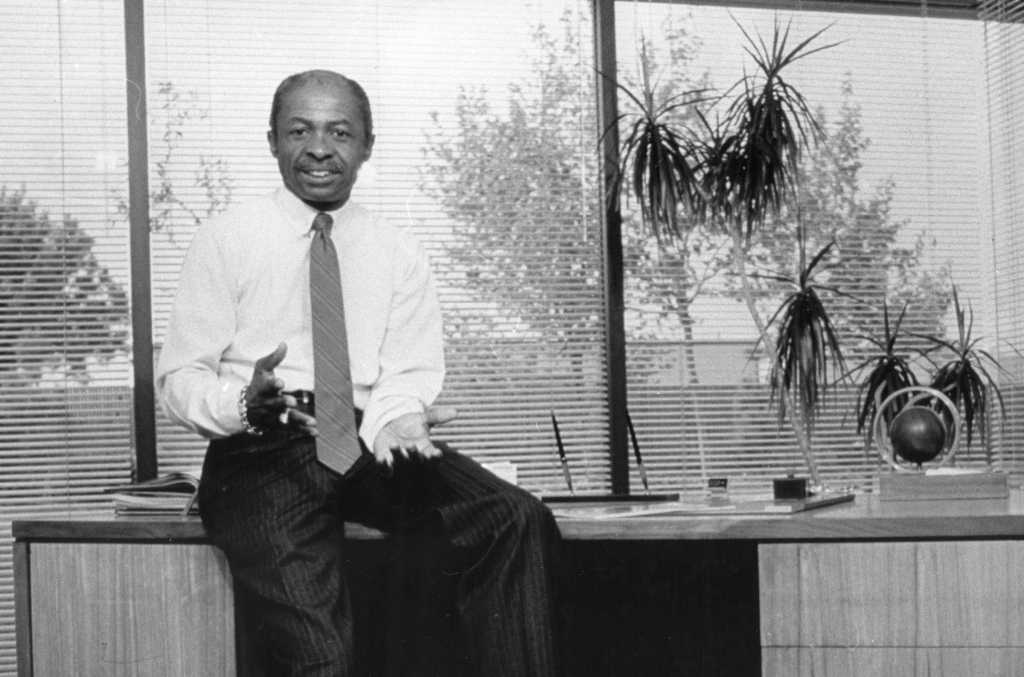

Roy L. Clay Sr.: Godfather of Silicon Valley

August 22, 1929 – September 22, 2024

Roy L. Clay Sr.

Palo Alto Historical Association

Roy Clay was one of nine children raised in a household without electricity or a toilet. He nonetheless grew up to become the one of the first Black Americans to graduate from St. Louis University, earning his degree in mathematics.

After being denied a job interview at McDonnell Aircraft Manufacturing on account of his skin color, Clay persisted in applying until he finally got a job. He worked at McDonnell as a computer programmer for two years, then joined Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where he wrote software to monitor an atomic explosion’s radiation diffusion. The reputation he developed there as a talented software developer landed him a job at Hewlett-Packard.

At HP, Clay wrote software for and led the development of the company’s first minicomputer, the 2116A, released in 1966. The computer and its immediate successors sold exceptionally well for decades, helping cement HP’s leadership in the early computer industry. Rising through the ranks at HP, Clay helped expand its talent pool by hiring engineers from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

Clay left HP in 1971 to start a consulting firm that advised the likes of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, a leading venture capital firm that helped shape Silicon Valley. In 1977, he formed his own company, ROD-L Electronics, a manufacturer of electrical safety test equipment. ROD-L hired a diverse workforce and offered employees a flex-time schedule as well as full tuition reimbursement. Said Clay, “If you’re not bothering to learn more, then you’re becoming unproductive.”

Clay was a pioneer not just in IT, but in politics: he was the first Black council member for the city of Palo Alto, California (1973–1979) and was elected to the position of city vice mayor (1976–1977).

As a trailblazer who worked tirelessly to diversify the tech industry, he earned the nickname “Godfather of Silicon Valley” — an honorific he adopted for his 2022 self-published memoir, Unstoppable: The Unlikely Story of a Silicon Valley Godfather.

Clay passed away at 95.

Ward Christensen: Modem maverick

October 23, 1945 – October 11, 2024

Ward Christensen

Jason Scott

Ward Christensen spent his entire 44-year career as a systems engineer at IBM — but it was his hobbies that earned him a place in history.

In 1977, when Christensen needed to convert a CP/M floppy disk to an audio cassette, he developed a transfer protocol consisting of 128-byte blocks, the sector size used by CP/M floppies. The protocol proved so versatile and reliable for a variety of platforms that it evolved into XMODEM, which became a standard for transferring data files across dial-up modem connections, especially at slower speeds such as 300 baud.

Christensen’s work on XMODEM earned him a sponsorship from the White Sands Missile Range to dial into the ARPANET. But he was frustrated by the organization’s design-by-committee approach, where ideas languished. When Chicago’s Great Blizzard of 1978 left Christensen and his fellow computing enthusiasts stranded in their homes, Christensen called his friend Randy Suess to develop a way for their local hobby computer club to meet virtually. The two collaborated, with Suess providing the hardware and Christensen the software. Within two weeks, the Computerized Bulletin Board System (CBBS) was up and running.

CBBS became the first of tens of thousands of dial-up BBSes that proliferated over the next twenty years. BBSes formed some of the first online communities and became important shareware distribution nodes for early game companies. The groundbreaking innovation earned Christensen multiple awards and recognition, including a 1993 Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Christensen retired from IBM in 2012, after which he remained active in Build-a-Blinkie, a nonprofit that teaches basic computer hardware skills. “I [can] think of no finer testimony to the soul behind this pioneer than the fact that up to the end of his life, he was teaching very young children how to solder together electronics to get them interested in science and engineering,” said Jason Scott, creator of BBS: The Documentary.

Christensen died at home from a heart attack at the age of 78.

Thomas E. Kurtz: Keeping it BASIC

February 22, 1928 – November 12, 2024

Thomas Kurtz

Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth

After earning his Ph.D., Thomas Kurtz joined Dartmouth College in 1956 as a mathematics professor and the director of the university’s computing center, which consisted of a single computer. Kurtz and colleague John Kemeny worked around this hardware limitation by developing the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System (DTSS), which operated from 1964 to 1999.

Having solved the problem of the computer’s accessibility, Kurtz and Kemeny set out to improve its usability for students. Existing programming languages such as FORTRAN and COBOL could be esoteric, so the pair developed an alternative: Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code, or BASIC. The school described the new language as “a simple combination of ordinary English and algebra, which can be mastered by the novice in a very few hours… There is enough power in the language BASIC to solve the most complicated computer problems.”

As a small, portable, easy-to-use language, BASIC proliferated, with variations for almost all platforms, becoming the introduction to software development for generations of computer users. It also launched countless careers and institutions: Microsoft BASIC was one of the first products from Microsoft when it was founded in 1975; the company later developed Applesoft BASIC to help launch Apple Computer’s Apple II personal computer. A young Richard Garriott used Applesoft to write the first Ultima computer role-playing game.

Kurtz retired from teaching in 1993. He received the IEEE’s Computer Pioneer Award in 1991 and was named an ACM Fellow in 1994. In 2023, he was inducted as a Computer History Museum Fellow, with Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates presenting the award. Dartmouth College produced a documentary about BASIC for the language’s 50th anniversary.

Kurtz died at 96 from sepsis.

Donald Bitzer: Platonic principles

January 1, 1934 – December 10, 2024

Donald Bitzer

NC State University College of Engineering

In 1959, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Control Systems Laboratory set out to develop a computerized learning system. They hired Don Bitzer, who’d just earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from the school.

Bitzer accomplished what a committee could not, and the result was Program Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations, or PLATO. The system was jam-packed with content, including tens of thousands of hours of course materials, Star Trek-inspired games, and a message board that constituted an early online community. The hardware, initially based on the ILLIAC I computer, was equally groundbreaking: PLATO was one of the first computers to combine a touchscreen with graphics, and it was an early example of timesharing — an innovation University of Illinois might’ve earned a patent for, had the paperwork not been misfiled.

In 1964, the PLATO IV model debuted another innovation: the flat-panel plasma display. This alternative to traditional cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays, invented by Bitzer, H. Gene Slottow, and Robert Willson, rippled far beyond academic computers: decades later, it became the basis for flatscreen, high-definition televisions, used in computers and entertainment worldwide. For this work, Bitzer received a 2002 Technology & Engineering Emmy Award.

In 1989, Bitzer joined the faculty of NC State University in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he remained until retirement. He was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2013, the National Academy of Inventors in 2018, and as a fellow of the Computer History Museum in 2022.

“He was a rare systems-level individual who could easily move between hardware and software, and wrangled both sets of people, all while evangelizing the entire PLATO platform to any individual or organization who would listen,” said Thom Cherryhomes, creator of IRATA.ONLINE, a modern online community based on the PLATO system.

Bitzer was 90 when he died at home.